A while back I went through my iTunes library and took the songs/albums/artists not already living in their own playlist and put them into a mega-playlist I called all of it. This way I could just hit “shuffle my library” when in my car and emulate what I used to do with my iPod. I don’t want to fuss with any UI, or play some algorithmically-generated playlist full of suggested music I might like. I just want to listen to my library, on shuffle.

But I’ve been feeling lately like shuffling just… isn’t good. Maybe the same artist plays twice in a row, or within just a couple minutes of my past listen. Or each shuffle still front-loads the same small selection of songs, so I don’t really get to explore the depths of my library. It’s not a large library (10,000 songs), but not small either, so why am I hearing the same old stuff? This is the 21st Century, is it really so hard to shuffle music?

The short answer is: no, it’s not. We can pretty much shuffle any list of things in an almost truly random fashion. But there are plenty of reasons shuffling doesn’t seem random. Humans are inherently pattern-seeking animals, and in a truly random sequence of songs, a given artist is no more or less likely to play next based on the previous artist. So you could have two artists play in a row—or if it’s truly random, the same song!

Another problem is that once software gets Good Enough™ it doesn’t usually get touched again until there are actual problems with it—or there is a strong monetary incentive to do so. So a developer with the task to write a shuffle feature might do what’s Good Enough™ to close the ticket according to the requirements and test plan, then move onto the next ticket.

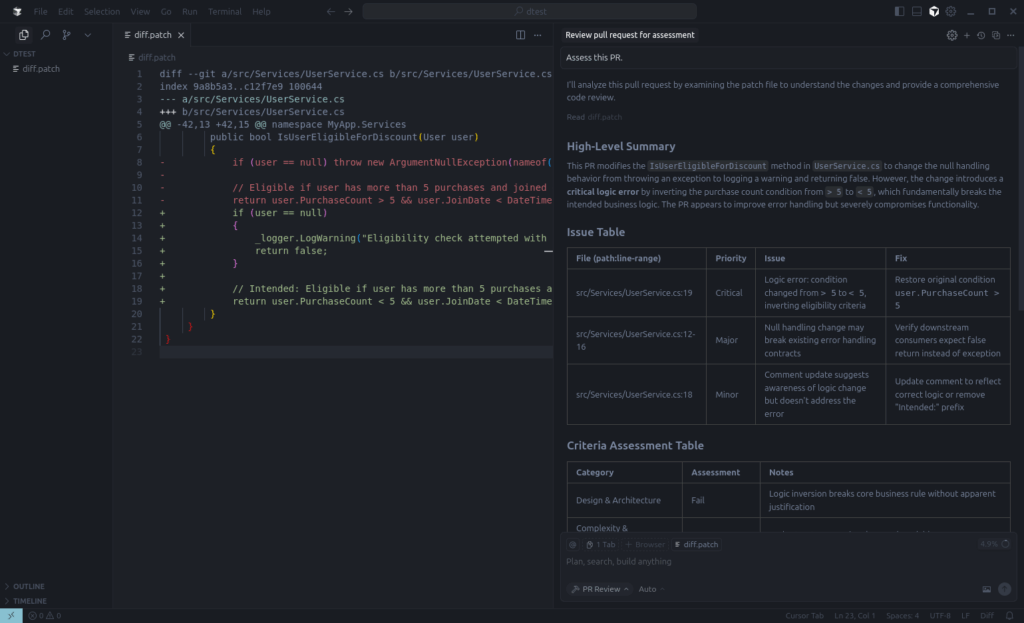

So what does it really take to do a good job shuffling a playlist? I wanted to do a little experimenting so I thought I would start from the ground up and walk through a few different methods. First, I need…

The Music

I took my playlist and ran it through TuneMyMusic to get a CSV. Then I wrote a little bit of code to parse that CSV into a list of Song objects, which would be my test subject for all the shuffling to come.

True Random

First I wanted to see how poorly, or how well, a “true” random shuffle worked. This is easy enough.

We’ll just do a simple loop. For the length of the song list, grab a random song from the list and return it:

for (var i = 0; i < songList.Count - 1; i++)

{

var index = RandomNumber.Next(0, songList.Count - 1);

yield return songList[index];

}

And right away I can see that the results are not good enough. Lots of song clustering, even repeats: one song right after the other!

[72]: Goldfinger - Superman

[73]: Metallica - Of Wolf And Man (Live with the SFSO)

[74]: Orville Peck - Bronco

[75]: Def Leppard - Hysteria

[76]: Kacey Musgraves - Follow Your Arrow

[77]: Kacey Musgraves - Follow Your Arrow

[78]: The Thermals - My Heart Went Cold

[79]: Miriam Vaga - Letting Go

A Better Random

After looking at the results from the first random shuffle, two requirements have become clear:

- The input list must have its items rearranged in a random sequence.

- Each item from the input list can only appear once in the output list.

Kind of like shuffling a deck of cards. I’d be surprised to see a Deuce of Spades twice after shuffling a deck. I’d also be surprised to see the same Kacey Musgraves song in my queue twice after hitting the shuffle button.

Luckily this is a problem that has been quite handily solved for quite a long time. In fact, it’s probably used as the “default” shuffling algorithm for most of the big streaming players. It’s called the Fisher-Yates shuffle and can be accomplished in just a couple lines of code.

for (var i = shuffledItemList.Length - 1; i >= 0; i--)

{

var j = RandomNumber.Next(0, i);

(shuffledItemList[i], shuffledItemList[j]) = (shuffledItemList[j], shuffledItemList[i]);

}

Starting from the end of the list, you swap an element with a random other element in that list. Here I’m using a tuple to do that “in place” without the use of a temporary variable.

The results are much better, and at first glance almost perfect! But scanning down the list of the first 100 items, I do see one problem:

[87]: CeeLo Green - It's OK

[88]: Metallica - Hero Of The Day (Live with the SFSO)

[89]: Metallica - Enter Sandman (Remastered)

[90]: Guns N' Roses - Yesterdays

It’s not the same song, but it is the same artist, and in a large playlist with lots of variety, I don’t really like this.

Radio Rules

Now I know I don’t want the same song to repeat, or the same artist, either. While we’re at it, let’s say no repeating albums, too. So that’s two new requirements:

- No more than x different songs from the same album in a row.

- No more than y different songs from the same artist in a row.

This is pretty similar to the DMCA restrictions set forth for livestreaming / internet radio. It will also help guarantee a better spread of music in the shuffled output.

Here’s some code to do just that:

var shuffledItemList = ItemList.ToArray();

var lastPickedItems = new Queue<T>();

for (var i = shuffledItemList.Length - 1; i >= 0; i--)

{

var j = RandomNumber.Next(0, i);

var retryCount = 0;

while (!IsValidPick(shuffledItemList[j], lastPickedItems) &&

retryCount < MaxRetryCount)

{

retryCount++;

j = RandomNumber.Next(0, i);

}

if (retryCount >= MaxRetryCount)

{

// short-circuiting; we maxed out our attempts

// so increment the counter and move on with life

invalidCount++;

if (invalidCount >= MaxInvalidCount)

{

checkValidPick = false;

}

}

// a winner has been chosen!

// trim the stack so it doesn't get too long

while (lastPickedItems.Count >= Math.Max(ConsecutiveAlbumMatchCount, ConsecutiveArtistMatchCount))

{

_ = lastPickedItems.TryDequeue(out _);

}

// then push our choice onto the stack

lastPickedItems.Enqueue(shuffledItemList[j]);

(shuffledItemList[i], shuffledItemList[j]) = (shuffledItemList[j], shuffledItemList[i]);

}

return shuffledItemList;

This, at its core, is the same shuffling algorithm, with a few extra steps.

First, we introduce a Queue, which is a First-In-First-Out collection, to hold the x most recently chosen songs.

Then when it’s time to choose a song, we look in our queue to determine if any of the recent songs match our criteria. If they do, then we skip this song and choose another random song. We attempt this only so many times. While the chance is low, there’s still a small chance that we could get stuck in a loop. So there’s a short-circuit built in that will tell the loop it’s done enough work and it’s time to move on.

In addition to that, there’s a flag with a wider scope: if we’ve short-circuited too frequently, then the function that checks for duplicates will stop checking.

This is an extra “just in case”, because if I hand over a playlist that’s just a single album or artist, I don’t want to do this check every single time I pick a new song. At one point it will become clear that it isn’t that kind of playlist.

Once a song has been chosen, the lastPickedItems Queue gets its oldest item dequeued and thrown to the wind, and the newest item is enqueued.

How does this do? Pretty well, I think.

[89]: Metallica - One (Remastered)

[90]: Stone Temple Pilots - Plush

[91]: Megadeth - Shadow of Deth

[92]: System of a Down - Sad Statue

[93]: Jewel - Don't

[94]: Def Leppard - Love Bites

[95]: Elton John - 16th Century Man (From "The Road To El Dorado" Soundtrack)

[96]: Daft Punk - Aerodynamic

[97]: Kacey Musgraves - High Horse

[98]: Above & Beyond - You Got To Go

[99]: Gnarls Barkley - Just a Thought

But not all playlists are a wide distribution of artists and genres. Sometimes you have a playlist that is, for example, a collection of 80s rock that’s just a bunch of Best Of compilations thrown together. How does this algorithm fare against a collection like that?

Answer: not well.

[0]: CAKE - Meanwhile, Rick James...

[1]: CAKE - Tougher Than It Is (Album Version)

[2]: Breaking Benjamin - I Will Not Bow

[3]: Enigma - Gravity Of Love

[4]: CAKE - Thrills

[5]: Clutch - Our Lady of Electric Light

It immediately short-circuits, and we see lots of clustering. Maybe not a deal-breaker for a smaller, more focused playlist, but I can’t help but feel there’s a better way to handle this.

Merge Shuffle

Going back to the deck of cards analogy: there are only 4 “albums” in a deck, but shuffling still produces good enough results for countless gamblers and gamers. So why not try the same approach here?

We want to split our list into n elements, then merge them back together, with a bit of randomness. Like cutting and riffling a deck of cards.

First, we’ll do the easy part: split up the list into a list of lists – like a bunch of hands of cards.

private List<List<T>> SplitList(IEnumerable<T> itemList, int splitCount)

{

var items = itemList.ToArray();

return items.Chunk(items.Length / splitCount).Select(songs => songs.ToList()).ToList();

}

Then, we pass this list to a function that will do the real work of shuffling and merging.

private IEnumerable<T> MergeLists(List<List<T>> lists)

{

var enumerable = lists.ToList();

var totalCount = enumerable.First().Count;

var minCount = enumerable.Last().Count;

var difference = totalCount - minCount;

var lastList = enumerable.Last();

lastList.AddRange(Enumerable.Repeat((T)dummySong, difference));

// set result

var resultList = new List<T>();

var slice = new Song[enumerable.Count];

for (var i = 0; i < totalCount - 1; i++)

{

for (var l = 0; l <= enumerable.Count - 1; l++)

{

slice[l] = enumerable[l][i];

}

for (var j = slice.Length - 1; j >= 0; j--)

{

var x = RandomNumber.Next(0, j);

(slice[x], slice[j]) = (slice[j], slice[x]);

}

for (var j = 1; j <= slice.Length - 1; j++)

{

if (slice[j - 1] == dummySong)

{

continue;

}

if (slice[j].ArtistName == slice[j - 1].ArtistName)

{

(slice[j - 1], slice[slice.Length - 1]) = (slice[slice.Length - 1], slice[j - 1]);

}

}

if (i > 0)

{

var retryCount = 0;

while (!IsValidPick(slice[0], resultList.TakeLast(1)) &&

retryCount < MaxRetryCount)

{

(slice[0], slice[enumerable.Count - 1]) = (slice[enumerable.Count - 1], slice[0]);

retryCount++;

}

}

resultList.AddRange((IEnumerable<T>)slice.Where(s => s != dummySong).ToList());

}

return resultList;

}

This is kind of a big boy. Let’s go through it step by step.

First, we cast our input list to a local variable. I am allergic to side-effects, so I want any changes (destructive or otherwise) confined to a local scope inside this function to keep it as pure as possible.

We’ll take the local list, and then find the length of the biggest chunk, and the length of the smallest chunk. There will only be one chunk smaller than the rest. We’ll fill it up with dummy songs so it’s the same length as the other chunks, and then disregard the dummy songs later.

Once our lists are in order, we slice through them one section at a time. The slice gets shuffled, then checked for our earlier-defined rules, but a little more relaxed: no artist or album twice in a row. If a song breaks a rule, we just move it to the end of the array and try again, always with a short-circuit so we don’t get caught in an endless loop.

And of course, we will always allow / ignore the dummy songs, so they don’t interfere with any real choice.

But, there’s a problem! Like a deck of cards, shuffling once just isn’t enough. Like you do with a real deck of cards, let’s go through this process at least seven times.

for (var i = 0; i <= ShuffleCount - 1; i++)

{

var splitLists = SplitList(list.ToList(), SplitCount);

list = MergeLists(splitLists);

}

And… the output looks really good, in my opinion!

[0]: Daft Punk - Digital Love

[1]: America - Sister Golden Hair

[2]: CAKE - Walk On By

[3]: Guns N' Roses - Yesterdays

[4]: Hey Ocean! - Be My Baby (Bonus Track)

[5]: CAKE - Meanwhile, Rick James...

[6]: Fitz and The Tantrums - Breakin' the Chains of Love

[7]: Digitalism - Battlecry

[8]: Harvey Danger - Flagpole Sitta

[9]: Guttermouth - I'm Destroying The World

However, this only really works well in the areas where the plain-old Fisher-Yates shuffle doesn’t. When used on smaller or more homogeneous sets, the results still leave something to be desired. These two shuffle methods complement each other, but cannot replace each other.

Shuffle Factory

So what happens now?

I thought about checking the entire playlist beforehand to see which algorithm should be used. But there’s no one-size-fits-all solution for this. Because, like my iTunes library, there could be a playlist with a huge number of albums, and also a huge number of completely unrelated singles.

So let’s get crazy and use both.

First we need to determine the boundary between the Fisher-Yates shuffle and the “Merge” Shuffle (for lack of a better term). I’m going to just use my instincts here instead of any hard analysis and say: if it’s a really small playlist, or if more than x percent of the playlist is one artist, then we’ll use the Merge Shuffle.

private ISortableList<T> GetSortType(IEnumerable<T> itemList)

{

var items = itemList.ToList();

if (HasLargeGroupings(items))

{

return new MergedShuffleList<T>(items);

}

return new FisherYatesList<T>(items);

}

public bool HasLargeGroupings(IEnumerable<T> itemList)

{

var items = itemList.ToList();

if (items.Count <= 10)

{

// item is essentially a single group (or album)

// no point in calculating.

return true;

}

var groups = items.GroupBy(s => s.ArtistName)

.Select(s => s.ToList())

.ToList();

var biggestGroupItemCount = groups.Max(s => s.Count);

var percentage = (double)biggestGroupItemCount / items.Count * 100;

return percentage >= 15;

}

Pretty straightforward! There is also the function that performs the check, and returns a new shuffler accordingly.

Now let’s shuffle.

public void ShuffleLongList(IEnumerable<T> itemList,

int itemChunkSize = 100)

{

var items = itemList.ToList();

if (items.Count <= itemChunkSize)

{

chunkedShuffledLists.Add(GetSortType(items).Sort().ToList());

return;

}

items = new FisherYatesList<T>(items).Sort().ToList();

// split into chunks

var chunks = items.Chunk(itemChunkSize).ToArray();

// shuffle the chunks

var shuffledChunks = new FisherYatesList<T[]>(chunks).Sort();

foreach (var chunk in shuffledChunks)

{

chunkedShuffledLists.Add(GetSortType(chunk).Sort().ToList());

}

}

Again, pretty simple.

Split our input into x lists of y chunk size (here, defalt to 100). Again we’ll do a little short-circuiting and say if the input is smaller than the chunk size, we’ll just figure out the shuffle type right away and exit immediately.

Otherwise, we do a simple shuffle of the input list and then split it into chunks of the desired size. I chose to do this preliminary shuffle as an extra degree of randomness. I hate hitting shuffle on a playlist, playing it, then coming back and shuffling again and getting the same songs at the start. So this will be an extra measure to guarantee the start sequence is different every time.

Next we shuffle the chunk ordering. Again, using Fisher-Yates, and again, for improved starting randomness.

After that we just iterate through the chunks and shuffle them according to whichever algorithm performs better for that particular chunk.

The output here is, again, really nice in my testing. I ran through and checked multiple chunks and felt overall very pleased with myself, if I’m being honest.

[0]: Rina Sawayama - Chosen Family

[1]: Clutch - Our Lady of Electric Light

[2]: Matchbox Twenty - Cold

[3]: Rocco DeLuca and The Burden - Bus Ride

[4]: Rob Thomas - Ever the Same

[5]: MIKA - Love Today

[6]: CeeLo Green - Satisfied

[7]: Metallica - For Whom The Bell Tolls (Remastered)

[8]: Elton John - I'm Still Standing

[9]: Rush - Closer To The Heart

...

[0]: Wax Fang - Avant Guardian Angel Dust

[1]: Journey - I'll Be Alright Without You

[2]: Linkin Park - High Voltage

[3]: TOOL - Schism

[4]: Daft Punk - Giorgio by Moroder

[5]: Fitz and The Tantrums - L.O.V.

[6]: Stone Temple Pilots - Vasoline (2019 Remaster)

[7]: Jewel - You Were Meant For Me

[8]: Butthole Surfers - Pepper

[9]: Collective Soul - No More No Less

Outtro

I don’t think there’s any farther I can take this. I know if I looked closer and the end results, I could find something else to change. There’s a whole world of shuffling algorithms out there, and plenty to learn from. If I felt so inclined I could write something to shuffle my playlists for me, but this exercise was really to learn first why shuffling never seemed good enough, and second if I could do better.

(The answers, as usual, were “it’s complicated” and “maybe”.)

Further Reading

- The source code for my work is over at my github.

- Spotify, once upon a time, did some work on their shuffling and wrote about it here

- Live365 has a brief blog post on shuffling and DMCA requirements here