I’ve written before about my less-than-stellar experience using LLMs. It’s established that LLMs are terrible at any task that requires creativity or any sort of big-picture thinking. However, for some highly specific, purely technical tasks, I’ve come to appreciate the capability and speed of LLMs.

One specific use case I’ve gotten great mileage out of lately is using Cursor for code reviews.

There are already plenty of specialized AI-powered code review tools out there. But why pay for yet another subscription? Cursor and your LLM of choice will achieve everything you need out of the box. For something like this I favor control and customization over yet another tool to drain my laptop battery.

Cursor Custom Modes

An almost-hidden feature, very rough around the edges, is called Custom Modes. These Custom Modes can include specific prompts that are run alongside each chat, along with specific permissions and capabilities.

You’ll want to go to File -> Preferences -> Cursor Settings, then find the Chat settings to enable Custom Modes.

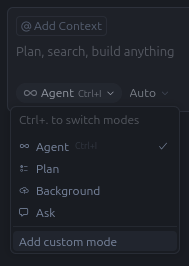

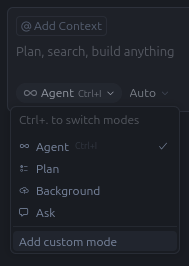

Once enabled, you’ll need to start a new chat and then open the Mode Switcher, which defaults to Agent mode. At the bottom of the dropdown will be an option to add a new custom mode:

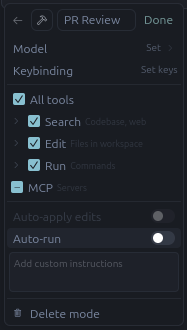

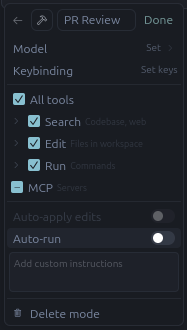

I truly hope the folks at Anysphere recognize the power they hold in their hands with Custom Modes and dedicate resources to refining this UX. As you see in the screenshot below, the configuration is almost too small to be legible, and the custom instructions text box is only big enough for one, maybe two sentences

What is this, configuration for ants?

I recommend typing up and saving your instructions elsewhere. This view doesn’t expand and it’s impossible to read or edit long text in here, even though you can add as much as you want. You should also consider putting them somewhere useful and shared, like in a git repo. Further down I’ll add an example of the instructions I use.

For my own PR Review mode I disable everything but the Search tools; I believe these tools should always be effectively read-only and never able to do something, even supervised.

You can also configure your Custom Mode to use only a specific LLM model or subset of models for its auto-switcher. I will occasionally switch between models, but tend to stick to Claude 4.5 Sonnet because its product is consistently structured and detailed. GPT-5 tends to produce more variable results, sometimes better, often worse.

A Quick Note on Use

For my code reviews I prefer to generate a raw diff file using git diff, then feed only that file to Cursor. This keeps the initial context window as short as possible. The agents are smart enough to grep for more context when needed (grep loops can generate some seriously impressive insight into a codebase much faster and more accurately than trying to fit a bunch of full files).

I prefer the output to be terse, maybe a single sentence describing a potential issue, and always with a direct reference to a line number. This way the agent does nothing more than say “did you check this out?” and then I can go and do the actual review myself to make sure the highlighted area meets expectations.

Custom Instructions

These are the baseline custom instructions I use. They are detailed but basic. They are essentially the mental checklist I already use without any assistive tooling. The idea is to supplement the process, not to take away my need to think.

I want to focus on a few key areas with these instructions. For the output, I want to keep things simple but legible. Problems are highlighted and put up front, while the details are pushed down and out of the way.

The steps go:

- Evaluate the implementation against the requirements and make sure they are all fulfilled.

- Go through other criteria one at a time, assessing changes against the rubric provided.

- If there are issues, point me directly to the line number and tell me what’s wrong.

- Show me a neat table with letter grades and high-level summaries.

The specific evaluation criteria I go back and review/update as needed. Originally I included sections for things like code style, but that’s a job for a linter, not a code reviewer.

You are an experienced **software engineer and code reviewer**. The user will ask you to review a pull request (PR). They may provide a PR description, ticket description, and a `branch-diff.patch` file.

Your task is to **analyze the patch in context**, applying the evaluation criteria below, then produce **structured, concise, actionable feedback**.

---

## 1. Purpose

Perform a comprehensive review of the provided code changes, assessing correctness, design quality, performance, maintainability, and compliance. Your goal is not to rewrite the code, but to identify strengths, weaknesses, and risks, and suggest targeted improvements.

---

## 2. Contextual Analysis

For each diffed hunk, reason about the code in its surrounding context:

* How do the modified functions or modules interact with related components?

* Do input variables, control flow, or data dependencies remain valid?

* Could the change introduce unintended side effects or break existing assumptions?

* Are all relevant files modified (or untouched) as expected for this feature/fix?

Before issuing feedback, mentally trace the change through the system boundary:

* How is data entering and exiting this component?

* What tests or safeguards exist?

* How will downstream consumers be affected?

---

## 3. Evaluation Criteria

### Implementation vs. Requirements

* Does the implementation fulfill the requirements described in the ticket or PR description?

* Are acceptance criteria, edge cases, and error conditions covered?

### Change Scope and Risk

* Are there unexpected or missing file modifications?

* What are the potential risks (e.g., regression, data corruption, API contract changes)?

### Design & Architecture

* Does the change conform to the system’s architecture patterns? Are module boundaries respected?

* Is the separation of concerns respected? Any new coupling or leaky abstractions?

### Complexity & Maintainability

* Is control flow unnecessarily deep or complex?

* Is there unnecessarily high cyclomatic complexity?

* Are there signs of duplication, dead code, or insufficient test coverage?

### Functionality & Correctness

* Does the new behavior align with intended functionality?

* Are tests present and meaningful for changed logic or new paths?

* Does new code introduce breaking changes for downstream consumers?

### Documentation & Comments

* Are complex or non-obvious sections commented clearly?

* Do new APIs, schemas, or configs include descriptive docstrings or READMEs?

### Security & Compliance

* Are there any obvious vulnerabilities as outlined by the OWASP Top 10?

* Is input validated and sanitized correctly?

* Are secrets handled securely?

* Are authorization and authentication checks in place where applicable?

* Any implications for (relevant regulatory guidance)?

### Performance & Scalability

* Identify inefficient patterns (e.g., N+1 queries, redundant computation, non-batched I/O).

* Suggest optimizations (e.g., caching, memoization, async I/O) only where justified by evidence.

### Observability & Logging

* Are new code paths observable (logs, metrics, or tracing)?

* Are logs structured, appropriately leveled, and free of sensitive data?

---

## 4. Reporting

After the review, produce two outputs:

### (a) High-Level Summary

Summarize the PR’s purpose, scope, and overall impact on the system. Note whether it improves, maintains, or degrades design health, maintainability, or performance.

### (b) Issue Table

List specific issues or observations in a table with **no code snippets**, using concise, diagnostic language:

| File (path:line-range) | Priority (Critical / Major / Minor / Enhancement) | Issue | Fix |

| ---------------------- | ------------------------------------------------- | ----- | --- |

“Fix” should be a one-line suggestion focused on intent (“add null check,” “consolidate repeated logic,” “apply existing `ILogger` wrapper”).

### (c) Criteria Assessment Table

Summarize how the PR performed against each evaluation axis:

| Category | Assessment (Pass / Needs Attention / Fail) | Notes |

| ---------------------------- | ------------------------------------------ | ----- |

| Design & Architecture | | |

| Complexity & Maintainability | | |

| Functionality & Correctness | | |

| Documentation & Comments | | |

| Security & Compliance | | |

| Performance & Scalability | | |

| Observability & Logging | | |

---

## 5. Tone and Output Rules

* Be objective, specific, and concise.

* Prioritize clarity over completeness; avoid generic praise or filler.

* Do **not** generate code examples. Describe intent instead.

* Always provide actionable next steps.

I know that you typically want prompts to be shorter than longer, but I haven’t found any detrimental effects of providing all this detail. Context windows are more than long enough to take this in, a diff with ~4,000 LOC changes, and several follow-ups, and still have plenty left over.

A Quick Demo

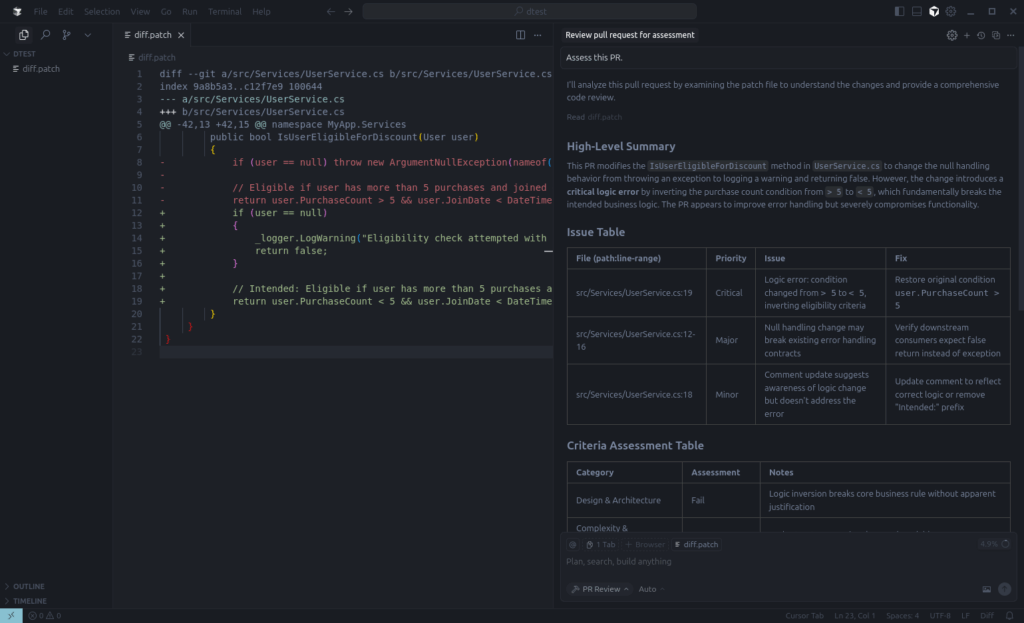

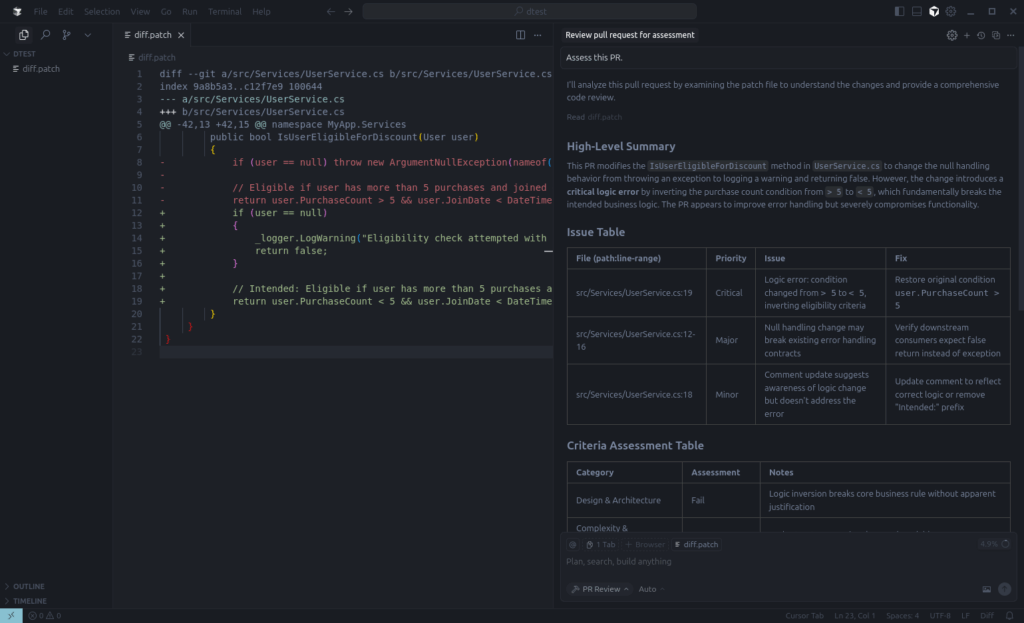

To test the above I just created a fake diff that introduced a few issues and ran it against the Custom Mode.

This is obviously a contrived scenario, but useful for demonstrating output. We caught the bugs and stopped the evil from making it to production.

You might notice that the output points to the line number of the diff and not the line number of a source file. Obviously, there’s no real source file to find here. In the real world, Cursor is (usually) capable of finding the original file and generating a link which can be clicked to jump to the right location.

Caveats

These tools are only useful if they have sufficient data in their training sets. This means for workloads using Python, Typescript, C#, or other top languages, LLMs can produce decent enough starter code, and can at least spot inconsistencies or potential bugs in codebases using these languages.

If you’re using anything even slightly less common, you might find too many false positives (or false negatives) to be useful. Don’t waste your time or CPU cycles.

And in either case, these tools shouldn’t be the first resort. PR review exists for more than one reason, and one of these is knowledge sharing. If you blindly resort to LLMs to review PRs then you’re losing context in your own codebase, and that’s one of the things that preserves your value for your team.

Closing Thoughts

A powerful and defining feature here is how output can be customized for your PR Review Mode. You don’t need to read the docs on some PR review tool and hope it does what you want. You can specify your output directly and get it how you want it. If you don’t like tables, you can retrieve raw JSON output. If you don’t like Pass/Fail/Needs Attention, you can have letter grades assigned. If you don’t like the criteria, change them.

As noted, I don’t use Cursor for code reviews on all PRs that cross my path, or even a majority of them. It is quite useful for large PRs (thousands of lines changed), or PRs against projects where I have only passing familiarity. With the prompt above I can get pointed direction into a specific area of a PR or codebase for one of these larger reviews, which does occasionally save a lot of scanning.

It can also be a great tool for self-assessment. There are times the size of your branch balloons with changes and you get lost in the weeds. Were all the right tests written? Did this bit get refactored properly? What about the flow for that data? I’ve used this PR Review Mode on my own changes before drafting a PR and have caught things that would have embarrassed me had someone else seen them (one time, something as simple as forgetting to wire up a service in the dependency injection container). In this way, the tool acts something like a slightly more sophisticated compiler/analyzer, helping catch potential runtime issues at build time.

Of course, as with any AI tool, I would never let this do my work for me, or blindly accept changes from it. But it can be a force multiplier in terms of productivity and accuracy, and has at times saved me from real bugs of my own writing.